Air Inequality

Air Pollution Is Much Worse Than You Might Think

👉🏽 At Vox, David Roberts reports on new research on the dramatic effect that US action on climate change would have on the health of US Americans:

The numbers are eye-popping. [Duke University climate scientist & IPCC report lead author Drew Shindell] testified: “Over the next 50 years, keeping to the 2°C pathway would prevent roughly 4.5 million premature deaths, about 3.5 million hospitalizations and emergency room visits, and approximately 300 million lost workdays in the US.”

He quotes from Shindell’s testimony to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform:

On average, this amounts to over $700 billion per year in benefits to the US from improved health and labor alone, far more than the cost of the energy transition.

In other words, dropping fossil fuels would pay for itself from an air quality perspective alone. Roberts makes the important point that although curtailing the warming effects of climate change requires globally coordinated action, the air quality benefits are local, making the rewards more directly tangible. He quotes Rebecca Saari, an air quality expert at the University of Waterloo, who says, “The air quality ‘co-benefits’ are generally so valuable that they exceed the cost of climate action, often many times over.”

So national (& even more local) level climate action will lead to outsized health and economic benefits from air quality improvements. And global air pollution hotspots like China and India stand to gain immeasurably from improving air quality.

And if this is true in the US — which, after all, has comparatively clean air — it is true tenfold for countries like China and India, where air quality remains abysmal. A Lancet Commission study in 2017 found that in 2015, air pollution killed 1.81 million people in India and 1.58 million in China.

Shindell’s research reveals that those estimates may be woefully low. [..] The true toll may be almost double that

👉🏽 If you’d like to follow updates on the air inequality crisis (with an emphasis on South Asia), here are some great Twitter accounts to follow: State of Global Air, Air Quality in India, Care for Air, Clean Air Fund, Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air, Air South Asia, Open Air Quality, Christa Hasenkopf, and Pallavi Pant.

The Deadly Mix of COVID-19, Air Pollution, and Inequality

👉🏽 Also at Vox, Lois Parshley has an excellent, sobering piece:

On April 5, a pre-print study released by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health directly linked air pollution to the probability of more severe Covid-19 cases. That joins decades of scientific literature that suggest race and income impact how much chronic air pollution you are exposed to. And it could be a major factor in the disproportionate Covid-19 mortality rates we’re now seeing in non-white populations.

In Louisiana, for example, black people represent 32 percent of the population and 70 percent of the Covid-19 deaths. In Wisconsin — in what its Gov. Tony Evers has called “a crisis within a crisis” — black people account for six percent of the population, and half of the Covid-19 deaths. In Michigan, 12 percent of residents are black, but account for 32 percent of deaths. Latinx populations show similarly disproportionate rates: in New York City, Hispanic people represent 29 percent of the population, and 34 percent of the city’s deaths — the largest percentage by race.

[..]

Mychal Johnson, a Bronx resident and co-founding member of the advocacy group South Bronx Unite, says that in the Bronx, “We already had higher rates of children missing school because they had to go to the hospital for respiratory problems.” Every year, the Bronx has 21 times more asthma hospitalizations than other New York boroughs, and over five times the national average.

The neighborhood, Johnson says, is known as “asthma alley,” and he and his family breathe the emissions of the hundreds of diesel trucks that stream from the neighborhood’s warehouses and along local highways. It is not unrelated that 44 percent of the Bronx is black. Nationwide, black children are 500 percent more likely to die from asthma than white children, and have a 250 percent higher hospitalization rate for the condition.

The article links to a pre-print study that finds that an increase of 1 μg/m3 in PM 2.5 (a relatively small increase in the most harmful category of air pollution, consisting of tiny particles with sizes under 2.5 microns) is associated with an 8% increase in the COVID-19 death rate.

Connecting the Dots Between Environmental Injustice and COVID-19

👉🏽 An excellent interview with Sacoby Wilson, a University of Maryland professor and scientist focusing on health issues related to environmental injustice, by Katherine Bagley in Yale e360.

Covid-19 has shown that we have a lot of Haves in this country, but we have a lot more Have-Nots. Our policies have disproportionally benefited the Haves while disproportionately impacting the Have-Nots. To address the disparities in Covid-19, we have to address our structural inequalities in this country. The first place to start is race and racism.

Wilson makes the point that scientific research is underserving the most vulnerable communities by failing to adequately assess the risk from more pollutants.

But what’s more egregious is we’re not really using advanced science to understand the true exposure profiles of those local populations. [..] So, PM2.5 is a pollutant that, it was shown in the Harvard study, could increase mortality rates with Covid-19. Now PM2.5 itself causes asthma, heart disease, stroke. It elevates blood pressure. It increases infant mortality rates. It can cause birth defects. It can cause low-birth-weight births. It also can cause diabetes, cancer, premature mortality. That’s PM2.5 by itself. What if you add ultra-fine particles? What if you add black carbon, which is a byproduct of diesel exhaust?

Does air pollution increase the risk of dying from COVID-19? (Yes.)

👉🏽 Damian Carrington at The Guardian reports on a new study by the UK Office for National Statistics of over 46,000 COVID deaths in England, showing that “a small, single-unit increase in people’s exposure to small-particle pollution over the previous decade may increase the death rate by up to 6%. A single-unit increase in nitrogen dioxide, which is at illegal levels in most urban areas, was linked to a 2% increase in death rates.”

So there’s a growing body of evidence that air pollution is linked to an increase in the COVID-19 mortality rate. When you couple this with the fact that non-white communities are more likely to live in areas with higher air pollution, this lays bare one more way in which the affects of fossil fuel consumption and COVID-19 are disproportionately borne by black and brown communities.

Heat Waves

👉 In NYT, Somini Sengupta has an unmissable piece on how heatwaves disproportionately impact poorer and more vulnerable populations, profiling refugees, laborers, farmers, immigrants, and elderly people across multiple continents.

In the United States, heat kills older people more than any other extreme weather event, including hurricanes, and the problem is part of an ignominious national pattern: Black people and Latinos like Mr. Velasquez are far more likely to live in the hottest parts of American cities.

His neighborhood is exceptionally vulnerable to heat extremes. According to the most recent available data, from 2018, Brownsville was among New York City’s hottest, with average daytime highs around two degrees Fahrenheit higher than the city as a whole.

Those neighborhoods are often the same areas that have faced some of the highest rates of coronavirus deaths. This spring, around 10 residents of Mr. Velasquez’s senior housing complex died from the virus.

“Inequality exacerbates climate and environmental risks,” said Kizzy Charles-Guzman, a deputy director for resilience efforts in the New York City Mayor’s office.

👉🏽 Lisa Collins at NYT reports on how a warming climate is changing the ecosystem of New York, causing difficulties for native plants, while subtropical plants are thriving, and invasive pests and weeds are growing out of control. This sentence blew my mind:

New York City, after years of being considered a humid continental climate, now sits within the humid subtropical climate zone. The classification requires that summers average above 72 degrees Fahrenheit — which New York’s have had since 1927 — and for winter months to stay above 27 degrees Fahrenheit, on average. The city has met that requirement for the last five years, despite the occasional cold snap. And the winters are only getting warmer.

👉🏽 At Yale E360, Jim Robbins looks at how a warming climate will impact agriculture and how researchers are trying to breed more resilient crops and livestock.

👉🏽 Baghdad’s record heat offers glimpse of world’s climate change future. By Louisa Loveluck and Chris Mooney in the Washington Post.

Warming in [Iraq] is far above average. Data from Berkeley Earth show that, compared with the country’s temperature at the close of the 19th century (1880-1899), the last five years were 2.3 degrees Celsius, or 4.1 degrees Fahrenheit, hotter. The Earth as a whole has only warmed by about half that amount over the same time period. [..]

A desert country like Iraq is warming more rapidly, explained MIT climate expert Elfatih Eltahir, because it is so dry. While additional heat in many places would partially go toward evaporating moisture in the soil, there just isn’t much such moisture in Iraq.

👉🏽 I also recommend checking out this 99% Invisible episode from January on Shade Inequality in Los Angeles.

Today, in Los Angeles, shade is distributed to people who can afford it. If you go into neighborhoods that were designed to be wealthy residential enclaves, the sidewalks are wider and include strips of grass four to ten feet wide, for the easy planting of thick, leafy trees.

Hancock Park, for example, is a flat neighborhood, landlocked in the center of the city. There is nothing about it that naturally lends itself over to being a lush, verdant tree canopy. But the neighborhood was developed as an exclusive, wealthy residential enclave. And when that happened, the power lines were moved underground and the layout was designed specifically to allow for tree growth. This is not the case for other large residential areas across Los Angeles.

Siberian Fires

👉🏽 On June 20, the town of Verkhoyansk in Siberia experienced a record-breaking high temperature of 38°C (100°F), the highest temperature recorded north of the Arctic Circle. A study published by the UK Met Office concluded that this would be extremely unlikely without human-caused climate change.

The results showed with high confidence that the January to June 2020 prolonged heat was made at least 600 times more likely as a result of human-induced climate change.

The study goes on to point out that

About 7,900 square miles of Siberian territory had burned so far this year as of June 25, compared to a total of 6,800 square miles as of the same date a year ago, according to official data, these fires led to a release of 56 Megatons of CO2 in June 2020, more than the yearly CO2 emissions of some countries (e.g., Switzerland).

👉🏽 Meanwhile, Andrew Kramer reported in the New York Times on one of the many environmental consequences of the warming Siberian permafrost.

Diesel fuel spilled from a tank that burst last week after settling into permafrost that had stood firm for years but gave way during a warm spring, Russian officials said. [..]

The spill released about 150,000 barrels of diesel into a river, compared with about 260,000 barrels of crude oil released into Prince William Sound during the Exxon tanker accident, a touchstone for environmental damage from petroleum spills.

👉🏽 Madeleine Stone reports in National Geoographic:

If fire becomes a regular occurrence on Siberia’s thawing tundra, it could dramatically reshape entire ecosystems, causing new species to take over and, perhaps, priming the land for more fires. The blazes themselves could also exacerbate global warming by burning deep into the soil and releasing carbon that has accumulated as frozen organic matter over hundreds of years.

“This is not yet a massive contribution to climate change,” says Thomas Smith, an environmental geographer at the London School of Economics who has been tracking the Siberian fires closely. “But it’s certainly a sign that something different is happening.”

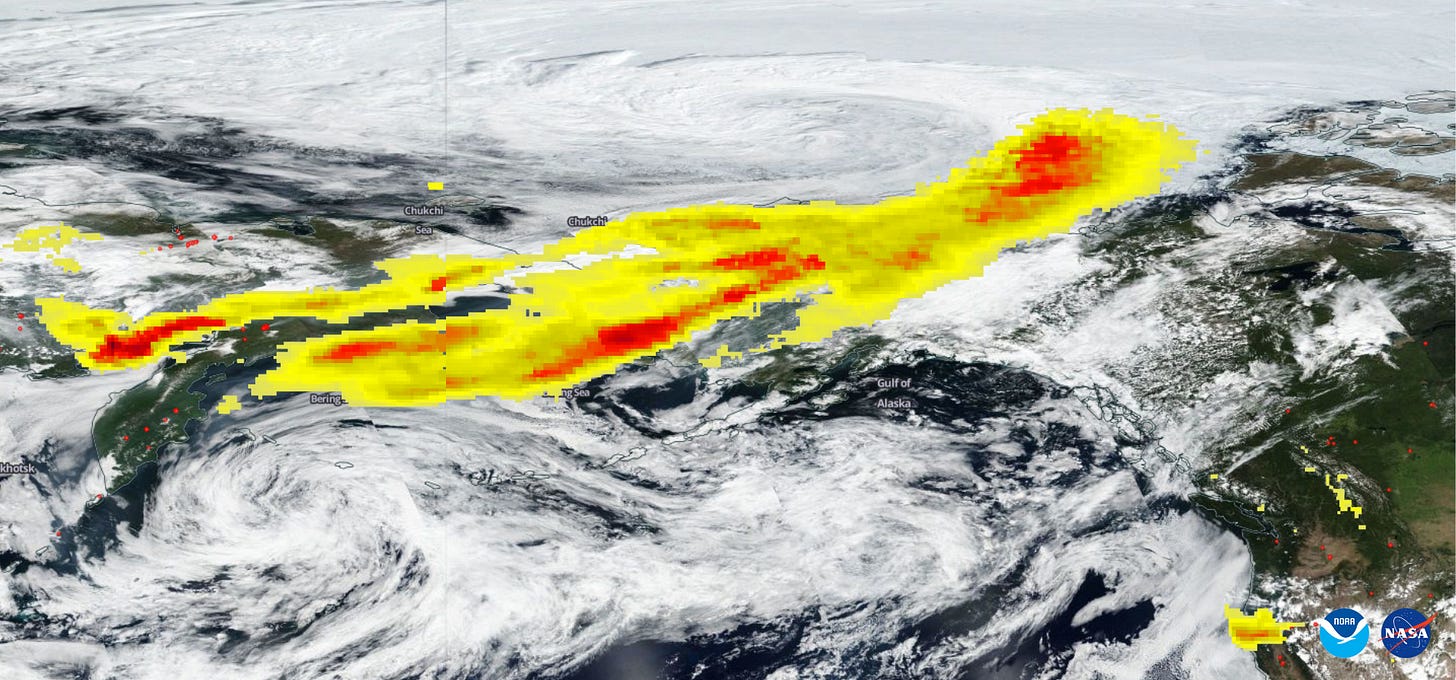

👉🏽 A NOAA NASA Satellite observed smoke from the Siberian fires extending all the way across the Bering Sea, and reaching Alaska.

Smoke and particulates from wildfires in Siberia extending all the way to Alaska. Image: NOAA/NASA

In Other Climate News

👉🏽 Leah Stokes is always great on summarizing climate policy:

👉🏽 Here’s a fascinating read by Cheryl Katz in Yale e360 digging in to the chemistry of Why Rising Acidification Poses a Special Peril for Warming Arctic Waters.

“The polar regions are especially vulnerable because of a systemic vulnerability that is linked to their chemical states today, which makes them very, very close to tipping over the edge into extremes of acidification,” says [climate scientist and IPCC report lead author Alessandro Tagliabue].

[..] As the carbonate levels in seawater decrease, mollusks and other shell-building creatures find it increasingly difficult to get enough ions to build and maintain their shells. And at a sufficiently low carbonate concentration — called undersaturation — the shells begin to corrode.

Models predict that large parts of the Arctic will cross this threshold as early as 2030, and researchers forecast that most Arctic waters will lack adequate aragonite for shell-building organisms by the 2080s.

👉🏽 On NPR’s On The Media, Vox writer David Roberts discusses how "shifting baselines syndrome" clouds our perspective on climate change.

👉🏽 Help Support My Writing 👈🏽

That’s all for this week! Apologies for the inadvertent 10-month-long hiatus in this newsletter (yikes!) I’ve been focusing my energy in 2020 on science writing work that helps me make rent (and also on trying to get by in this pandemic, just like everyone else).

On that note, I recently created a Patreon page. If you’d like to support my writing and be the first to know about all of my science communication projects, please consider becoming a patron. I simply can’t do the work I do without your support.

As a heads up, I’m also planning to add paid subscriptions to this newsletter to help support my climate writing — more on that soon. So if you’re primarily interested in supporting my climate work, that might be a better option for you.

And if you’re not in a position to contribute, that’s totally fine as well! Thank you so much for reading, and for showing up. ✌🏽💜